MANY PEOPLE in Contra Costa County could hardly believe their ears that summer in 1900 when they first heard that Concord was mounting a campaign to steal the county seat from Martinez.

“The little farming hamlet of Concord is not even an incorporated city . . . . It doesn’t have a sewer,” editorialized the Martinez hometown paper, the Contra Costa Gazette.

The Pinole Times said:

“It (Concord) is a nice quiet town, and an excellent place to go if you want a rest cure, but it is not our choice for the county seat.”

Those sentiments didn’t seem to make an impression on A. W. Maltby, former Chicago hotel man turned Concord rancher. He had dreams, and they included making Concord the county seat.

Maltby, a native of England, always wanted to own a ranch out west. In 1899, at the age of 40, he swapped his Chicago hotel for a parcel of Concord land owned by Sam Hopkins. He also bought the adjoining property owned by Concepcion Soto, daughter of Salvio Pacheco, amassing 800 acres in alland then with his family Maltby moved west.

He had only been in town a year when he realized there had to be a better way to get crops to Oakland than with horse and wagon. He envisioned an electric railroad piercing the Oakland — Berkeley Hills and stretching into central Contra Costa. If Concord was the county seat, it would be easier to get backers.

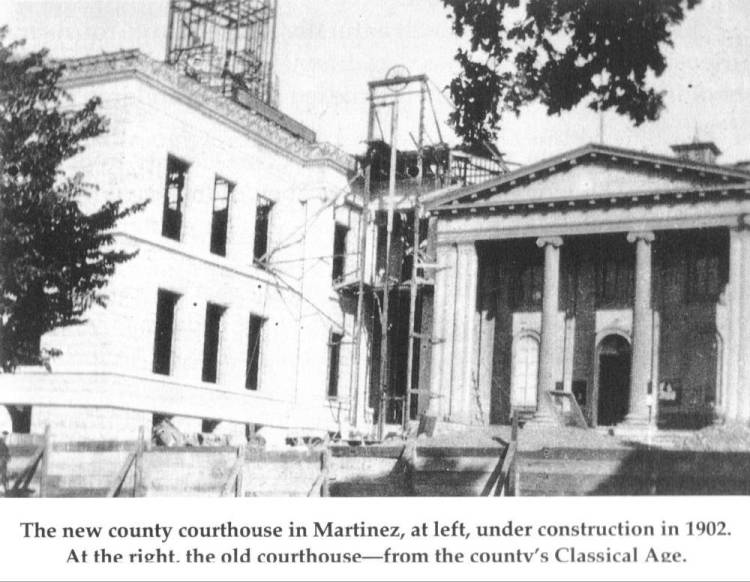

An event in Martinez boosted Maltby’s idea. The 46-year-old county courthouse was in sad shape. Six successive grand juries had condemned the brick building. In the spring of 1900, $100,000 was voted for a new building.

Maltby reasoned that since the county was going to build a new courthouse anyway, why not put it in Concord – the center of the county. He offered 10 acres as a site for the new courthouse, and put up $5,000 in cash.

Concord Justice of the Peace J. J. Burke, olive grower J. F. Busey, blacksmith Joseph Boyd, and rancher Robert Caven helped circulate petitions, collecting the 1,792 signatures needed to get the measure on the ballot.

The group promised to put up between $25,000 and $50,000 to help pay for the new building.

The supervisors accepted the petitions and set the election for November 1900 — to coincide with the presidential election.

Martinez attorney W. S. Tinning cried foul, claiming that some signers had registered after the petition had been filed. In other cases the same person had done all the signing for the different members of his family. Two hundred of the signatures shouldn’t be counted, said Tinning.

Burke argued that the supervisors didn’t have the authority to pull the issue from the ballot. Only the courts had that power, he said.

After two months of controversy and a hearing that lasted into the evening, the Concord group suddenly withdrew its petition. The very next day Burke had 16 men on the streets collecting signatures all over again. Within 10 days enough signatures had been collected. The supervisors voted again to put the measure on the ballot.

The editor of the Contra Costa Gazette was horrified.

“Do you want increased taxes? Do you want to see the county seat removed from the most central place in the county? Do you want to incommode yourself for the next 50 years? . . . Do you want the money of the county to be used for the advantage of the people of Alameda County?”

The Gazette reported that Concord businessmen had met with the Merchants Exchange of Oakland.

They (Concord businessmen) promised that if the county seat was removed to Concord, fine roads would be built to the county line, and everything done that would help divert the trade of Contra Costa to Oakland.

The Gazette was scornful of Maltby’s gift of land. It reported on good authority that the offer had dwindled from the original 10 acres to three acres.

“This small tract of land of three acres is valued by the real estate boomers of Concord at $10,000, but any one can go into the open market at any other time and buy it for at least $500,” the paper wrote.

The Martinez paper scoffed at the idea of an electric railroad. It predicted that if it came to pass, Contra Costans would have to pay the $400,000 it would cost.

“Every sensible person will naturally refuse to vote for such a proposition. They do not want additional burdens placed on the shoulders of themselves, their children or their children’s children.”

On November 6, the men in Contra Costa County trooped to the polls. The women stayed home. They didn’t have the vote yet. The Gazette announced the vote – 2,112 for Martinez and 1,223 for Concord.

Maltby, however, didn’t give up on the electric railway. On January 13, 1909, Maltby headed a list of the eight men who put $2 million together and incorporated the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern Railway.

On September 3, 1913 the first electric trains rolled from Sacramento through Concord to Oakland. Martinez was not part of the system.

You must be logged in to post a comment.