Captains of boats carrying freight up the Sacramento River, and bringing down cargoes of produce, fruit, grain and hay, found places to discharge and load far apart in the early days.

In 1848 and 1849 sloops and schooners, drawing only a few feet, carried the shipments. Unique to San Francisco Bay and its tributaries, the flat bottom scows moved easily in and out of the creeks and over river bars.

By 1850 steam vessels were arriving. They didn’t replace the scows but rather carried larger and heavier cargoes, but they required deep water docks.

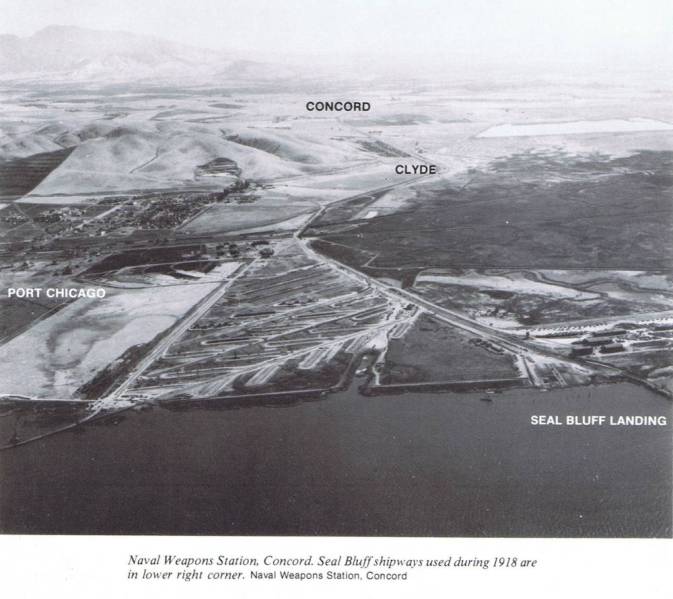

The first practical site upriver from Martinez to berth a steamer was five miles above the county seat at a point called “Seal Bluff.” A dock built here was in water deep enough for vessels to come in and load full shipments. The virgin soil of Mount Diablo, Clayton and Ygnacio valleys yielded heavy crops of barley and wheat, and teamsters delivered the yield to the dock at Seal Bluff Landing.

Among the settlers in the early 1850s were four brothers, Newton, Asa, Simeon and Philo Woodruff. Another Woodruff, David S., came in 1858 and taught school in the village.

Samuel S. Bacon took up 160 acres in 1855 and farmed there until 1860, when he moved over to Pacheco to become a shopkeeper. He returned in 1868 and with a partner built a 50- by 100-foot warehouse.

While the surrounding area remained in agriculture for over 100 years, industry came slowly to the community. One of the earliest was a smelter, built in 1890 for Copper King, Ltd. Ore came from a mine twenty-eight miles east of Fresno. Unfortunately the company’s assayer was less than competent, and his decisions forced the company into bankruptcy. He ran off with an actress, leaving his wife and seven children in Seal Bluff.

A boost of mammoth proportions came to the village in 1907 when the C. A. Smith Lumber Company of Coos Bay, Oregon, bought 1,500 acres on one and a half miles of river frontage. The company built a planing mill, a dry kiln, and drying sheds and in total had one of the largest finishing mills anywhere in the United States. Its annual payroll came to nearly $300,000. For its employees’ convenience the firm established the “City of Bay Point,” retiring the name Seal Bluff Landing.

A fire in 1913 destroyed all the improvements, but the company reorganized and opened two years later as the Coos Bay Lumber Company. It operated until 1932, when the demand for lumber ceased as a result of the Great Depression.

Although the fire put a stop to many community improvements, the town already had two churches, Saint Francis’ Catholic Church and the Community Congregational Church. To fill the need for a library, the lumber company provided space for the town’s 113 books in its hospital room. The Odd Fellows Hall was built in 1911, as was a moving picture theater, established by Andy Shirpke. The twostory California Hotel was built in 1916 by the Heinz Brothers. At this time Saturday night dances were a regular feature of the town; they were held at Biel Hall.

One feature of the refinancing out of which came the Coos Bay Lumber Company was a deed restriction written by the former owner prohibiting the sale of liquor on any of its property. The Coos Bay firm got around it by financing the construction of a bar on .land not included in the sales agreement. Coos Bay turned the bar over to a club of Bay Point citizens, requiring that all profits”. . . shall be used for the benefit of all the people of Bay Point.”

By 1917 Bay Point housed about one thousand people, and that year the biggest change in the town took place. The United States War Department awarded a contract to build ten 10,000ton freighters to the Pacific Coast Shipbuilding Company. The German Uboats were sinking so many Allied vessels carrying food and war materiel to Europe, replacements were needed even if they came from the Pacific Coast.

On January 6, 1918, the company broke ground for eight ship ways, a plate shop and auxiliary buildings. The Southern Pacific brought workers from Oakland and Berkeley, and the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern carried others from all along its Contra Costa line.

Additional employees meant a need for local housing. The shipyard founded the town of “Clyde,” reminiscent of the world’s greatest shipbuilding river of the same name in Scotland. The firm built 120 cottages, to provide some housing for its nearly forty-five hundred men. It hired noted architect Bernard Maybeck to design a hotel. When completed, the three-story structure had 176 rooms and a basement with a seventeen-lane bowling alley.

The largest freighter ever built on the Pacific Coast up to the time was launched as the Diablo. It slid down the ways on November 30, 1918, nineteen days after the war ended. The Pacific Coast Shipbuilding Company deserted the town, the Clyde Hotel closed its doors, and the Coos Bay Lumber Company moved to Oakland. But most of the residents, many of whom had opened businesses, stayed on. Others found employment in Concord or at the oil refineries at Avon and Martinez. Even a few new businesses came to town. One, the Bay Point Iron Works, employed men to cast iron, brass, bronze and aluminum. The local school employed six teachers. A newspaper, the Bay Point Breeze, was founded by Charles B. Hodgkins, and life went on tranquilly for most inhabitants, with only superficial problems. Yet the town changed its name in 1931 to “Port Chicago.”

The change to end all changes began in 1942. In June of that year the War Department established its naval ammunition depot and built its ship loading docks on Port Chicago’s waterfront. For two years of World War II, the facility shipped ammunition needed by the armed forces fighting the war in the Pacific.

Two ships, tied up on opposite sides of the loading dock to receive ammunition, exploded on the evening of July 17, 1944. In a blinding roar, between five and ten thousand tons of ammunition killed 369 sailors, vaporizing many. Almost all of them were black.

One sailor jumped up and slid down the stairs on his stomach, got over a ten-foot fence topped with barbed wire, scrambled through all kinds of shattered glass in his bare feet, and suffered only a scratched fingernail.

Every seat was filled in the movie house a half mile away, and even though an outer wall buckled, nothing fell on the 192 people under the ceiling. A steward off one of the ships was having a drink at a tavern. The concussion broke his glass and blew him across the room. Nearby an eighteen-month-old infant boy slept in his crib as a fifty-pound piece of ship plate tore a hole through the roof of a house next door and ricocheted through his wall, cutting the legs off his little bed. When the parents, cut and bleeding, found their son, he was still sleeping on the mattress, which was resting on the floor.

Every building in Port Chicago was damaged; phone lines came down; power lines blazed; and gas escaped from open pipes. In Walnut Creek, twelve miles away, folding glass doors of a market blew off their hinges. Windows were blown out even in San Leandro. Three miles away a lookout on. a tanker going downstream was blown into the bay.

At the time of the blast Port Chicago contained 660 homes, three hotels, a movie house, and a shopping district.

In spite of all the trauma the residents suffered, few moved away. They rebuilt and went on with their lives, collecting an average of $1,300 each for damage to 300 homes in the town. Twenty years later, when the navy wanted to buy them out, Port Chicago residents resisted with every tool at their disposal. Between 1966 and 1968 the United States government bought 5,000 acres, first some as a buffer zone between the docks and the ammunition depot, and eventually the town itself.

In 1969 the government evicted the last owner and demolished the town.

You must be logged in to post a comment.